Most people assume that before a generic drug hits the shelf, it must be tested on real people to prove it works the same as the brand-name version. That’s not always true. In fact, the FDA regularly approves generic drugs without a single human trial - and it’s all thanks to something called a bioequivalence waiver, or biowaiver.

These waivers let drugmakers skip expensive and time-consuming in vivo studies (those done in people) if they can prove, through lab tests, that their product behaves the same way in the body as the original. It’s not a loophole. It’s science. And it’s saving the generic drug industry millions - and getting life-saving medications to patients faster.

How Bioequivalence Waivers Work

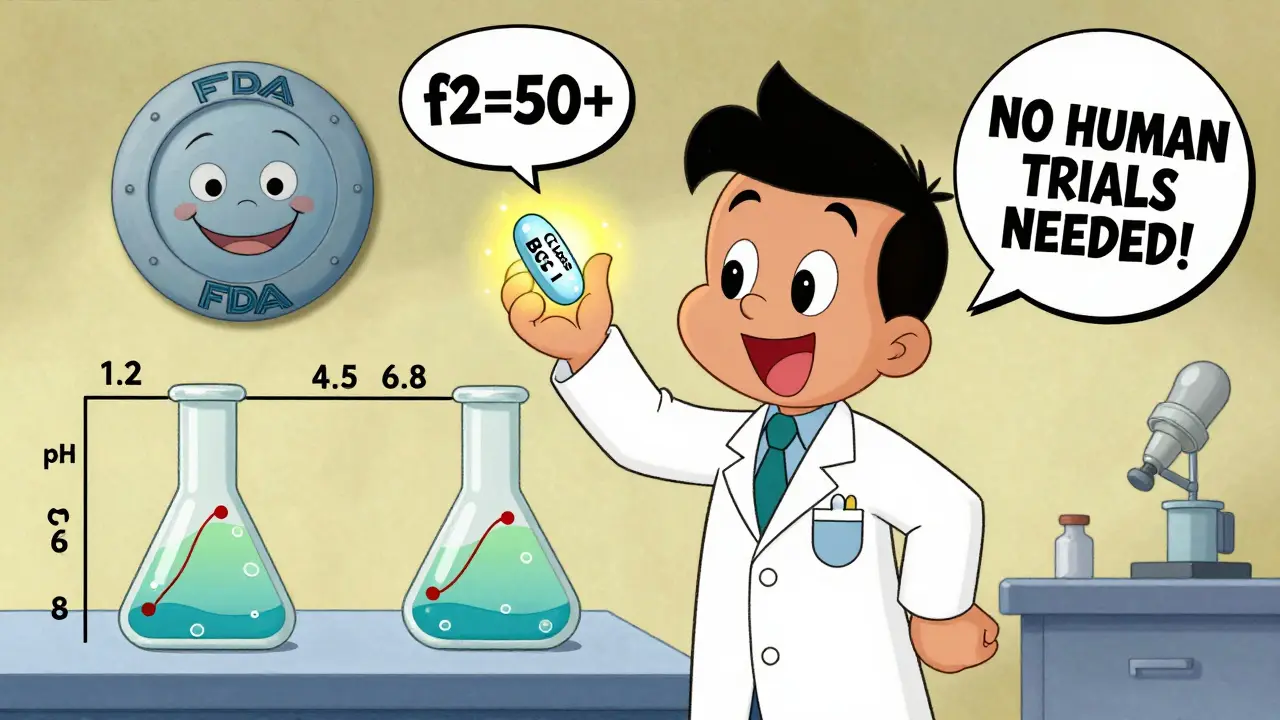

The FDA doesn’t just say, “Sure, no human testing.” There’s a strict, science-backed process. The key is the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). This system sorts drugs into four classes based on two things: how well they dissolve in water (solubility) and how easily they cross into the bloodstream (permeability).

Drugs in BCS Class I are the golden ticket for waivers. These are drugs that are highly soluble and highly permeable. Think ibuprofen, metformin, or atenolol. For these, the body absorbs them so reliably that what matters most is how fast the pill breaks down in your stomach - not what happens after.

That’s where in vitro (lab-based) dissolution testing comes in. Instead of giving 24 people the drug and measuring their blood levels over 24 hours, manufacturers test how quickly their pill dissolves in simulated stomach fluids at different pH levels (1.2, 4.5, and 6.8). If the generic dissolves at the same rate and to the same extent as the brand-name drug - and if both are BCS Class I - the FDA accepts that as proof of bioequivalence.

It’s not guesswork. The FDA requires matching dissolution profiles using a statistical measure called the f2 similarity factor. The value must be 50 or higher. That means the dissolution curves are nearly identical across all time points. If they’re not, the waiver gets rejected.

Who Benefits - and How Much

For generic drug companies, skipping human trials is a game-changer. A single in vivo bioequivalence study costs between $250,000 and $500,000. It takes 6 to 12 months. Multiply that by the dozens of products a company might develop, and you’re talking tens of millions in savings.

According to FDA data from 2022, about 18% of all Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) for solid oral products used a biowaiver. That’s up from 12% in 2018. Each waiver saves roughly 8 to 10 months in approval time. That means generic versions of drugs like lisinopril or levothyroxine reach the market faster - often before the brand-name patent even expires.

That speed translates to lower prices. IQVIA estimates that biowaivers contribute to $1.2 billion in annual savings across the U.S. generic drug market. Patients don’t pay more because the FDA lets companies cut development costs. That’s the direct link between regulatory science and pharmacy savings.

What About Other Drug Classes?

BCS Class I drugs are the easy case. But what about drugs that don’t dissolve well (Class II) or don’t absorb well (Class III)?

Class III drugs - those with high solubility but low permeability - can sometimes qualify. But only if they meet extra conditions: identical excipients (inactive ingredients), no site-specific absorption, and matching dissolution profiles. Even then, the FDA is cautious. In 2021, 35% of biowaiver rejections for Class III drugs came down to inadequate dissolution methods that couldn’t detect small formulation differences.

Class II drugs - like many cholesterol or diabetes meds - are almost never eligible. Their absorption depends on how well they dissolve, which varies wildly between formulations. That’s why you still see human trials for drugs like simvastatin or glimepiride.

And forget about modified-release pills. The current waiver rules don’t cover extended-release, delayed-release, or enteric-coated products. The FDA says the science isn’t mature enough yet. A pilot program is exploring this for a few narrow cases, but it’s still early.

Why This Matters for Patients

You might think, “If they’re not testing on people, how do we know it works?” The answer is: because we’ve tested it on hundreds of similar drugs over the last 20 years.

A 2020 study in the AAPS Journal found that for BCS Class I drugs, in vitro testing predicted in vivo results with over 95% accuracy. That’s better than many clinical studies. The FDA has approved over 1,500 biowaivers since 2017. Very few have led to post-market safety issues.

For patients, this means more generic options, sooner. When a drug like metformin becomes available as a generic six months earlier, pharmacies can offer it for $5 instead of $40. Insurance plans lower copays. Patients stick with their treatment. It’s a quiet win - no headlines, no ads - just better access.

Challenges and Criticisms

It’s not perfect. Some companies report inconsistent decisions across FDA review divisions. A submission approved in one office might get rejected in another - even with identical data. A 2022 PhRMA survey found 42% of firms experienced this inconsistency.

Another issue: method development. Setting up a good dissolution test isn’t easy. It takes 2 to 3 months just to validate the method. Many small companies lack the staff or equipment. That’s why big generics like Teva and Mylan use biowaivers in 25-30% of their pipelines, while smaller firms use them in only 10-15%.

The FDA’s own internal reports show that 35% of rejected applications failed because the dissolution test wasn’t discriminating enough. That means it couldn’t tell the difference between a good formulation and a bad one. A test that’s too forgiving can let subpar products slip through.

That’s why early consultation with the FDA - through the Pre-ANDA program - is critical. Companies that meet with regulators before submitting have a 22% higher approval rate.

The Future: What’s Next?

The FDA isn’t stopping here. Its 2023-2027 strategic plan aims to expand biowaiver opportunities by 25%. That includes:

- Refining BCS criteria to include more Class III drugs

- Developing better in vitro-in vivo correlation models

- Piloting waivers for certain narrow therapeutic index drugs (like some antiepileptics)

By 2027, experts predict biowaivers could be used in 25-30% of all ANDAs - up from 18% today. That means even more generic drugs, faster.

But there’s a catch: complex products. Modified-release tablets, patches, inhalers, and injectables still require human trials. The science for those is still evolving. For now, biowaivers remain limited to simple, immediate-release pills.

Bottom Line

Bioequivalence waivers aren’t about cutting corners. They’re about using smarter science. When a drug is highly soluble and highly permeable, its behavior in the body is predictable. That means a lab test can replace a human trial - safely, reliably, and cost-effectively.

For patients, this means more affordable medicines, sooner. For manufacturers, it means less waste, faster approvals. For the FDA, it’s a win-win: fewer unnecessary human studies, and stronger confidence in generic drug quality.

It’s not magic. It’s method. And it’s working.

What drugs are eligible for a bioequivalence waiver?

Only immediate-release solid oral dosage forms that meet the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) criteria. BCS Class I drugs (high solubility, high permeability) are the most common. Some BCS Class III drugs (high solubility, low permeability) may qualify if they have identical excipients and no site-specific absorption. Modified-release, injectable, or topical products are not eligible.

How do you prove bioequivalence without human trials?

By using in vitro dissolution testing under physiologically relevant conditions (pH 1.2, 4.5, and 6.8). The generic and brand-name drug must have nearly identical dissolution profiles across multiple time points (10, 15, 20, 30, 45, and 60 minutes). The f2 similarity factor must be 50 or higher, meaning the curves are statistically similar.

Why doesn’t the FDA require human testing for all generics?

Because for certain drugs - especially BCS Class I - in vitro testing is more accurate, sensitive, and reproducible than in vivo studies. Human trials are expensive, time-consuming, and ethically unnecessary when science shows the drug’s behavior is predictable. The FDA’s goal is to reduce unnecessary testing without compromising safety.

Are bioequivalence waivers safe?

Yes. Over 1,500 biowaivers have been approved since 2017 with very few post-market safety issues. A 2020 study showed 95% concordance between in vitro results and actual human outcomes for BCS Class I drugs. The FDA monitors these products closely after approval.

Can I get a generic drug approved faster with a waiver?

Absolutely. Skipping an in vivo study can cut approval time by 8-10 months. For a generic company, that means bringing a drug to market over half a year sooner. For patients, it means lower prices and earlier access.

Why are some biowaiver applications rejected?

The most common reasons are: (1) dissolution methods aren’t discriminatory enough to detect formulation differences, (2) the f2 similarity factor is below 50, (3) excipients differ between products, or (4) the drug doesn’t meet BCS Class I or III criteria. Poorly designed studies are the biggest cause of rejection.

Do all generic drug companies use bioequivalence waivers?

No. Large companies like Teva and Mylan use biowaivers in 25-30% of their pipelines because they have the resources. Smaller companies use them in only 10-15% due to lack of staff, equipment, or expertise in dissolution method development. The barrier isn’t the rule - it’s the science.

Simon Critchley

February 8, 2026 AT 22:58Whoa, this is wild 🤯 - the FDA basically lets Big Pharma skip human trials if your drug dissolves like sugar in hot tea. BCS Class I? More like BCS ‘Blessed Class I’! I’m just glad they’re not letting us get away with ‘close enough’ for opioids or anticoagulants. But seriously, if ibuprofen dissolves at 50 f2, why are we still doing 24-patient trials? 🤔

Tom Forwood

February 10, 2026 AT 12:50yo so like i just got my generic metformin and was like ‘wait… did they even test this on a person??’ and then i read this and now i feel like a genius 😎 turns out science is smarter than i am. also lowkey love that this saves $1.2B a year. my copay went from $45 to $7. thank u, FDA. 🙌

John McDonald

February 12, 2026 AT 10:06This is one of those quiet wins that nobody talks about but changes lives. I work in a clinic, and I’ve seen patients stop meds because they couldn’t afford them. When generics hit faster, people stay on treatment. No drama, no headlines - just a guy in Ohio taking his lisinopril for $3 instead of $40. That’s the real MVP of pharma regulation.

Joshua Smith

February 14, 2026 AT 05:20Interesting. I’ve always wondered how the FDA handles this. The f2 factor thing is fascinating - 50+ means the curves are nearly identical. I’d love to see the actual dissolution curves for a few examples. Maybe there’s a public database? Also, how do they handle batch-to-batch variation? Seems like a tiny shift could slip through.

Monica Warnick

February 15, 2026 AT 19:07OMG I just found out the FDA lets them skip human trials?! I thought they were testing on actual humans! This is like a horror movie. What if the generic pill doesn’t dissolve right? What if it’s a scam? I’m never taking another generic again. My heart is racing. 😭

Ashlyn Ellison

February 15, 2026 AT 20:54Simple: if the pill breaks down the same way in a glass of water as the brand, and the body absorbs it the same way, why test on people? It’s not magic. It’s chemistry. And it’s saving lives.

Ryan Vargas

February 16, 2026 AT 20:11Let me get this straight - the FDA approves generic drugs without human testing… based on a dissolution test? That’s not science. That’s corporate lobbying disguised as regulatory policy. Who’s funding the dissolution labs? Are they the same companies that own the original patents? What’s to stop them from tweaking excipients just enough to pass the test but still be toxic? This smells like a controlled release… of corporate profit.

Sam Dickison

February 18, 2026 AT 11:20Big pharma’s got a whole playbook here - BCS Class I = free pass. But the real win? The FDA’s being smart. They’re not cutting corners, they’re cutting the fluff. I’ve seen dissolution methods get rejected because they couldn’t tell the difference between a good pill and a bad one. That’s why method validation is everything. If your test can’t detect a 5% variation, you’re not doing your job.

Karianne Jackson

February 19, 2026 AT 17:38Wait… so they just test it in water? No humans? That’s it? I’m scared. What if my generic blood pressure pill doesn’t work? I’m gonna die. 😱

Chelsea Cook

February 19, 2026 AT 20:51Oh honey, you think this is wild? Wait till you find out the FDA lets them skip testing for 18% of all generics. That’s like saying, ‘Hey, this banana looks like the other banana, so we’ll just assume it tastes the same.’ But guess what? It works. And your insulin just got $20 cheaper. So shut up and take your pills. 💅

Andy Cortez

February 20, 2026 AT 08:04so i read this and im like… wait… so the fda just says ‘yep this dissolves same’ and calls it a day? what if the generic has weird fillers? what if it’s made in a basement in bangladesh? i’m not taking my pills anymore. i’m switching to homeopathy. 🤡

Jacob den Hollander

February 21, 2026 AT 13:23This is actually one of the most beautiful examples of regulatory science in action. The FDA didn’t just say ‘trust us’ - they built a whole framework: BCS, f2, pH profiles. They’re using physics and chemistry to replace animal and human trials where it’s safe. That’s not laziness - that’s innovation. And it’s why so many of us can afford our meds. Thank you, scientists.

glenn mendoza

February 22, 2026 AT 23:48It is with profound respect for the scientific rigor of the Food and Drug Administration that I acknowledge the elegance of the bioequivalence waiver paradigm. The Biopharmaceutics Classification System, grounded in empirical physicochemical principles, provides a robust, non-inferior alternative to in vivo bioequivalence studies for BCS Class I compounds. The statistical fidelity of the f2 similarity factor, when properly validated, ensures regulatory confidence without unnecessary human experimentation. This is not a loophole - it is a triumph of evidence-based policy.

Randy Harkins

February 24, 2026 AT 09:03Yessssss!! 🙌 This is why I love science. No human trials? No problem. As long as the pill dissolves like magic in your stomach (and it does), why make people swallow pills just to prove it? Also, $1.2B saved? That’s like giving every American a free coffee. ☕❤️

Chima Ifeanyi

February 25, 2026 AT 14:00Let me break this down for you: this isn’t science - it’s a corporate tax loophole with a lab coat. The FDA approves waivers because it’s cheaper to let Chinese manufacturers cut corners. You think they’re testing pH at 6.8? Nah. They’re dumping the powder in hot water and calling it a day. Meanwhile, patients are getting substandard generics. This is systemic failure disguised as efficiency. Wake up.