Vaginal Surgery Candidacy Checker

Assessment Questions

Result

When a woman’s pelvic floor can’t hold its shape any longer, the daily discomfort can feel endless. Vaginal surgery offers a direct, uterus‑preserving way to restore support without a big abdominal incision. Below you’ll learn exactly how it works, who it helps most, and what to expect after the operating room.

Quick Take

- Vaginal surgery repairs prolapse through the birth canal, avoiding large abdominal cuts.

- Common procedures include uterosacral ligament suspension, sacrospinous fixation, and colpocleisis.

- Ideal for women with stage II‑III prolapse who prefer a shorter hospital stay.

- Recovery typically takes 4‑6 weeks; most resume light activities within two weeks.

- Risks include mesh erosion (if used), urinary issues, and rare recurrence.

Understanding Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse is a condition where the uterus, bladder, rectum, or vaginal walls slip down into or out of the vaginal canal because the pelvic floor muscles and ligaments become weakened. It affects up to 50% of women over 50, but only about 10% develop symptoms severe enough to need treatment. Typical complaints include a sense of heaviness, bulging tissue, urinary leakage, and sexual discomfort. The severity is staged from I (mild) to IV (complete organ descent) using the POP‑Q (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification) system.

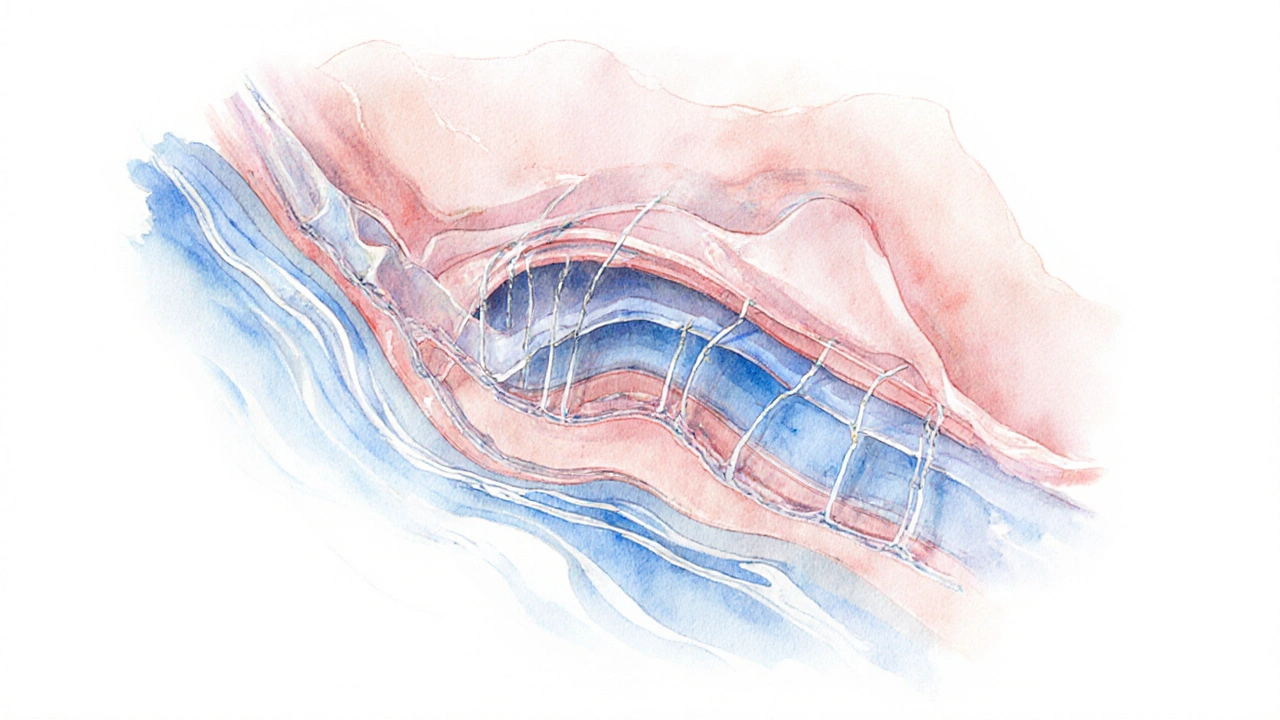

What Is Vaginal Surgery for POP?

Vaginal surgery treats prolapse by accessing the problem through the vagina rather than opening the abdomen. This approach preserves the uterus (unless removal is medically required) and usually shortens operative time and hospital stay. The surgery can be performed under general or regional anesthesia and often uses native tissue repair-stitching existing ligaments to restore support. In some cases, surgeons augment the repair with a synthetic or biological mesh, though mesh use has become more selective after FDA warnings.

Common Vaginal Procedures

Below are the most frequently performed vaginal techniques, each targeting a different support structure.

- Uterosacral ligament suspension re‑attaches the uterosacral ligaments to the vaginal apex, offering strong support for both the uterus and vaginal cuff. Success rates hover around 85% at five years.

- Sacrospinous ligament fixation ties the vaginal vault to the sacrospinous ligament on one side of the pelvis. It’s a good option when the uterosacral ligaments are too damaged.

- Transvaginal mesh repair places a lightweight polypropylene mesh to reinforce the anterior vaginal wall. Modern mesh is placed with a narrow strip and removed if erosion occurs, but many surgeons now prefer native‑tissue methods because of lower complication rates.

- Colpocleisis (partial colpectomy) closes the vaginal canal in women who no longer desire intercourse, offering a quick, durable fix for severe prolapse.

Who Benefits Most? Candidacy Criteria

Vaginal surgery shines for patients who meet these practical considerations:

- Stage II‑III prolapse where the apex or anterior wall is the main issue.

- Desire to keep the uterus (unless contraindicated by cancer or severe fibroids).

- Need for a short recovery-most outpatient or overnight stays.

- Limited abdominal surgical history that might make a laparoscopic approach risky.

- Acceptable anesthesia risk profile (regional or light general anesthesia).

Women with severe stage IV prolapse, extensive scar tissue from prior abdominal surgeries, or concomitant severe urinary incontinence may be steered toward an abdominal sacrocolpopexy instead.

Risks, Recovery, and Long‑Term Outcomes

All surgeries carry some risk. For vaginal POP repair, the most reported complications are:

- Short‑term urinary retention (10‑15%); often resolves with catheter drainage.

- De novo stress urinary incontinence (5‑12%).

- Mesh erosion or exposure (when mesh is used) - rates dropped to <2% with newer lightweight designs.

- Pain at the ligament fixation site (especially sacrospinous).

- Recurrence of prolapse (roughly 15‑20% at five years for native‑tissue repairs).

Recovery usually follows a predictable timeline:

- Day 0‑2: Hospital observation; light ambulation is encouraged.

- Week 1‑2: Limited lifting (<10lbs), avoid intercourse and strenuous exercise.

- Week 3‑4: Gradual return to normal activities; pelvic floor physical therapy can start.

- Month 2‑3: Full activity resume, including cardio and strength training.

Long‑term success hinges on postoperative pelvic‑floor rehabilitation, weight management, and avoiding chronic constipation.

Comparing Vaginal to Other Surgical Routes

| Aspect | Vaginal Surgery | Abdominal Sacrocolpopexy | Robotic/Minimally Invasive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incision Size | None (through vagina) | 10‑12cm abdominal cut | 5‑7mm ports |

| Hospital Stay | Outpatient or 1 night | 2‑3 nights | 1‑2 nights |

| Recovery Time | 4‑6 weeks | 6‑8 weeks | 5‑7 weeks |

| Uterus Preservation | Often retained | Usually retained | Usually retained |

| Mesh Use | Selective, lightweight | Synthetic mesh (larger surface) | Synthetic or biologic mesh |

| Complication Rate | ~10‑15% (mostly urinary) | ~12‑18% (including bowel injury) | ~10‑14% (similar to abdominal) |

| Long‑Term Success | 80‑85% at 5yr | 90‑95% at 5yr | ~88% at 5yr |

Choosing the right route depends on the patient’s anatomy, lifestyle goals, and surgeon expertise. Vaginal repair offers the fastest bounce‑back, while abdominal sacrocolpopexy still tops the durability charts for high‑grade prolapse.

After Surgery: Lifestyle & Follow‑Up

Even after a smooth operation, the pelvic floor needs ongoing care. Here’s a concise checklist:

- Start pelvic‑floor exercises (Kegels) within two weeks-ideally under a therapist’s guidance.

- Maintain a healthy weight; excess abdominal pressure can undo repairs.

- Avoid chronic constipation-incorporate fiber and adequate hydration.

- Schedule a postoperative visit at six weeks, then yearly exams to monitor for recurrence.

- Discuss any new urinary symptoms promptly; early intervention can prevent worsening.

Women who have had a colpocleisis should also have a routine exam to ensure the closure remains intact and to screen for vaginal atrophy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can vaginal surgery be done if I still want children?

Most vaginal POP repairs preserve the uterus and the vaginal canal, but they are not designed for future pregnancies. If childbearing is still a goal, doctors usually recommend non‑surgical pelvic‑floor therapy first and reserve surgery for after completing childbearing.

Is mesh always used in vaginal POP repair?

No. Modern practice favors native‑tissue repair whenever possible. Mesh is reserved for high‑risk cases where tissue quality is poor, and even then surgeons opt for lightweight, low‑profile designs to limit erosion.

How long does the operation itself take?

Typical vaginal POP surgery lasts 45‑90 minutes, depending on the number of compartments addressed and whether mesh is used.

Will I need another surgery later?

Recurrence rates average 15‑20% at five years for native‑tissue repairs. If prolapse returns, a repeat vaginal repair or a switch to abdominal sacrocolpopexy is possible.

Can I resume sexual activity soon after?

Most surgeons advise waiting 4‑6 weeks to allow tissues to heal fully. Lubricants and pelvic‑floor exercises can ease the return to intimacy.

Lily Saeli

September 29, 2025 AT 13:07When we weigh the options of surgery, the body itself asks for respect, and we must listen. Vaginal routes honor the natural pathways that have carried us through life, avoiding scars that shout of intrusion. The moral choice, then, is to seek methods that preserve function without unnecessary aggression. Simplicity in the approach reflects humility, and humility is a virtue we should cherish.

Joshua Brown

October 9, 2025 AT 10:53Let’s dive deeper into the anatomy, because understanding the floor’s architecture can demystify the whole process, and you’ll see why a vaginal route often makes sense, especially when the prolapse is moderate, and the patient wishes to keep her uterus. First, the uterosacral ligament suspension provides a sturdy anchor, and it’s performed through a small incision, reducing recovery time, and minimizing blood loss. Second, sacrospinous fixation offers an alternative when the posterior ligaments are compromised, and it can be done under regional anesthesia, which many patients prefer. Lastly, if a surgeon feels mesh is necessary, modern lightweight options exist, but they require meticulous placement, and close follow‑up, to guard against erosion.

andrew bigdick

October 18, 2025 AT 17:06It’s useful to remember that every person’s pelvic story is unique, and the decision shouldn’t be forced into a one‑size‑fits‑all box. If you’re comfortable keeping the uterus, the vaginal methods often align with personal goals, while still delivering solid support. For those who have had prior abdominal surgery, the vaginal corridor spares you the re‑opening of old scars, which can feel like a psychological relief as well as a physical one. Ultimately, the best plan respects the individual’s lifestyle, preferences, and health profile.

Leon Wood

October 26, 2025 AT 18:33Imagine stepping out of the operating room feeling like you’ve reclaimed a piece of yourself – that’s the power of a well‑executed vaginal repair! The recovery may be swift, but the real victory is the renewed confidence when you sit, stand, and move without that nagging heaviness. Let’s celebrate each small milestone: the first painless stroll, the gentle return to yoga, the smile when you realize intimacy is back on the table. Keep your eyes on the horizon, because with the right surgeon and mindset, you’re on the fast track to a stronger, happier you.

George Embaid

November 2, 2025 AT 17:13From a broader perspective, the choice of surgical route often mirrors cultural attitudes toward bodily integrity and medical intervention. In some communities, preserving the uterus is seen as essential to identity, while in others the focus is purely on functional outcome. The vaginal approach bridges these views by offering a minimally invasive path that respects both anatomy and personal values. Discussing these nuances with a knowledgeable practitioner ensures that the selected technique aligns with both medical evidence and individual belief systems.

Darrell Wardsteele

November 8, 2025 AT 12:06Let’s get the facts straight: mesh, when used, must be low‑weight, and it should never be left dangling where it can irritate tissue. Some surgeons still rely on outdated, heavy‑weight meshh, which is a recipe for erosion – and that’s simply unacceptable. The proper term is “vaginal mesh repair,” not “vaginal meshes repair,” and you want to ask for evidence‑based outcomes before signing any consent form. Moreover, the anesthesia risk must be assessed honestly; a superficial “yes” without a thorough pre‑op eval is reckless. In short, demand precision, demand transparency, and don’t settle for anything less.

Madeline Leech

November 13, 2025 AT 03:13We cannot ignore the fact that many of these procedures are pushed by a global medical elite that doesn’t care about the American woman’s right to choose a natural, uterus‑preserving solution. The data clearly show that low‑tech vaginal repairs outperform expensive abdominal sacrocolpopexies when performed by skilled hands, yet insurance companies keep funneling patients toward the costlier option. It’s time to stand up, demand honest counseling, and reject the narrative that only high‑tech equals high‑quality. Our bodies deserve respect, not a manufactured dependency on foreign‑made implants.

Barry White Jr

November 17, 2025 AT 18:20Vaginal repairs get you back faster.

Andrea Rivarola

November 22, 2025 AT 09:26I’ve been following the evolution of pelvic floor surgery for over a decade, and the shift toward native‑tissue vaginal repairs feels like a return to fundamentals that many of us have long yearned for. When I first learned about uterosacral ligament suspension, I was struck by how the surgeon could re‑anchor the apex using the body’s own ligaments, thereby avoiding the pitfalls associated with synthetic reinforcement. The sacrospinous fixation, on the other hand, offers a clever workaround when posterior support is compromised, and its simplicity often translates into shorter operative times. Over the years, I have observed that patients who undergo these procedures tend to report a quicker return to daily activities, which aligns with the data suggesting a median recovery of about two weeks for light tasks. Moreover, the psychological benefit of preserving the uterus cannot be overstated; many women view it as a symbolic preservation of femininity and reproductive identity, even when childbearing is no longer a priority. In contrast, the abdominal sacrocolpopexy, while effective, typically requires a longer hospital stay and a more extensive incision, which can be a deterrent for those wary of abdominal surgery. It is also worth noting that the use of mesh has become highly scrutinized after numerous reports of erosion, prompting a cautious approach that many surgeons now favor. Consequently, the modern trend leans heavily on meticulous suturing techniques, reinforcing the importance of surgical skill over reliance on foreign material. From a cost perspective, vaginal surgeries generally incur lower expenses, a factor that resonates strongly in our current healthcare economy. Patient satisfaction scores also tend to be higher for vaginal routes, primarily because the postoperative pain is often less severe and the scar burden is minimal. However, it is essential to recognize that not every case is suitable for a vaginal approach; severe stage IV prolapse or extensive pelvic scarring may necessitate an abdominal route for durable correction. The decision‑making process should therefore be a collaborative dialogue, integrating the surgeon’s expertise, the patient’s preferences, and the anatomical realities presented by the prolapse staging. In my experience, when this dialogue is grounded in transparent information, patients feel empowered to make choices that align with their values and lifestyle. Ultimately, the goal remains the same: restoring pelvic integrity, alleviating symptoms, and improving quality of life, regardless of the specific surgical corridor employed. Continued research and long‑term follow‑up will further clarify the optimal indications for each technique.

Tristan Francis

November 27, 2025 AT 00:33There’s a hidden agenda pushing high‑tech abdominal surgeries; the industry wants to sell more expensive kits while ignoring the simple, effective vaginal options that keep patients away from costly implants.