When a patient switches from a brand-name drug to a generic version, most people assume it’s the same thing. But for NTI drugs-narrow therapeutic index drugs-that assumption can be dangerous. These are medications where the difference between an effective dose and a toxic one is razor-thin. A small change in how the body absorbs the drug can mean the difference between controlling a seizure, preventing organ rejection, or sending a patient into the hospital.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) isn’t a luxury here. It’s a safety net. And with the rise of generic NTI drugs-especially in countries pushing for cost-cutting in healthcare-TDM has become one of the last lines of defense for patient safety.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

NTI stands for narrow therapeutic index. That means the range between a therapeutic dose and a toxic dose is very small. Even a 10-20% change in blood levels can cause harm. Common NTI drugs include warfarin (a blood thinner), digoxin (for heart failure), phenytoin (for seizures), lithium (for bipolar disorder), and cyclosporine (for transplant patients).

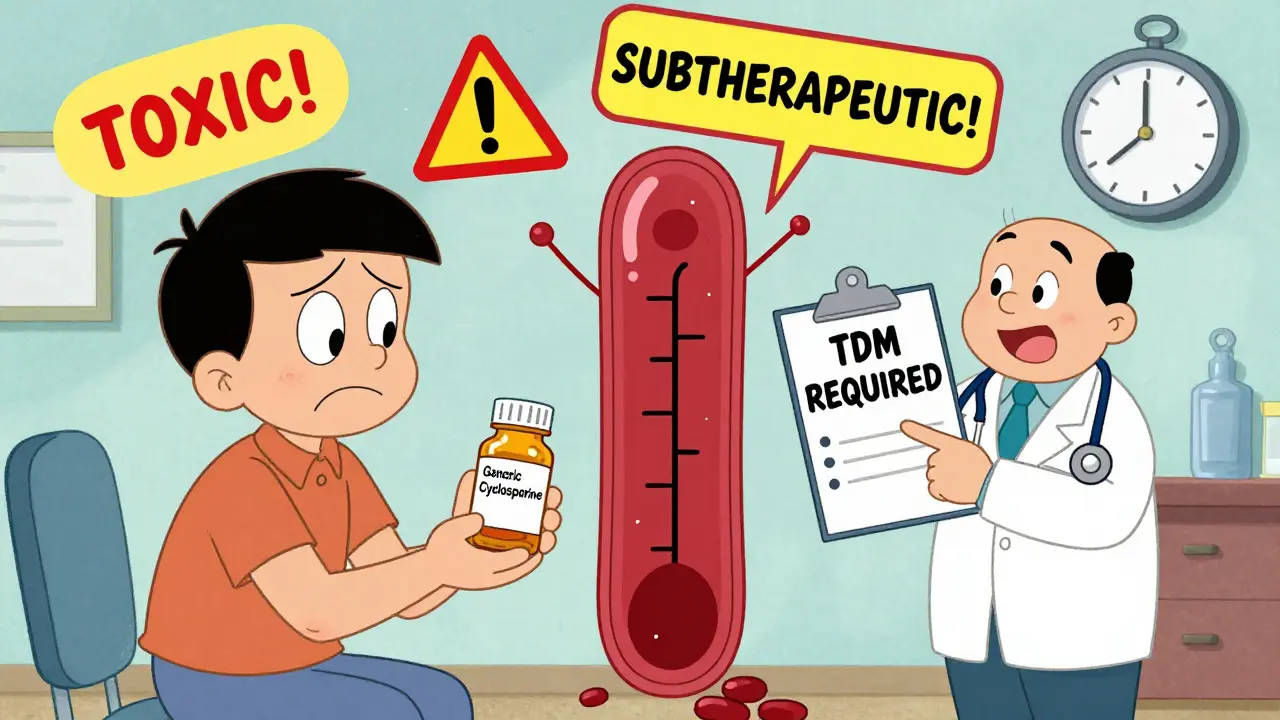

These drugs don’t have a wide safety margin. Take warfarin: too little, and a patient risks a stroke. Too much, and they could bleed internally. The same goes for cyclosporine. A level just 0.5 mcg/mL above the target can cause kidney damage. A level 0.3 mcg/mL below, and the body starts rejecting the new organ.

Generic versions of these drugs are required to be bioequivalent to the brand-name version-meaning they must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream within a certain range. But that range? It’s 80-125% of the brand. For most drugs, that’s fine. For NTI drugs, that’s a red flag.

Two generics might both meet the 80-125% rule, but if a patient switches back and forth between them, their blood levels can swing wildly. One generic might absorb faster. Another might release slower. The result? Unpredictable drug levels. And in NTI drugs, unpredictability equals risk.

Why TDM Is the Only Reliable Check

Doctors rely on lab tests to monitor drug levels. That’s TDM. It’s not about guessing. It’s about measuring. A blood sample is taken at a specific time-usually right before the next dose (trough level)-and sent to a lab that uses precise methods to detect exactly how much drug is in the bloodstream.

For NTI drugs, TDM isn’t optional. It’s standard. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the International Society of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Toxicology both recommend TDM for all NTI drugs, regardless of whether they’re brand or generic.

But here’s the problem: many clinics don’t do it. Why? Cost. Time. Lack of awareness.

A TDM test can cost $150-$400 depending on the drug and location. Results can take 3-10 days. Many primary care providers don’t have the training to interpret the results. So they assume: if the patient feels fine, the drug is working.

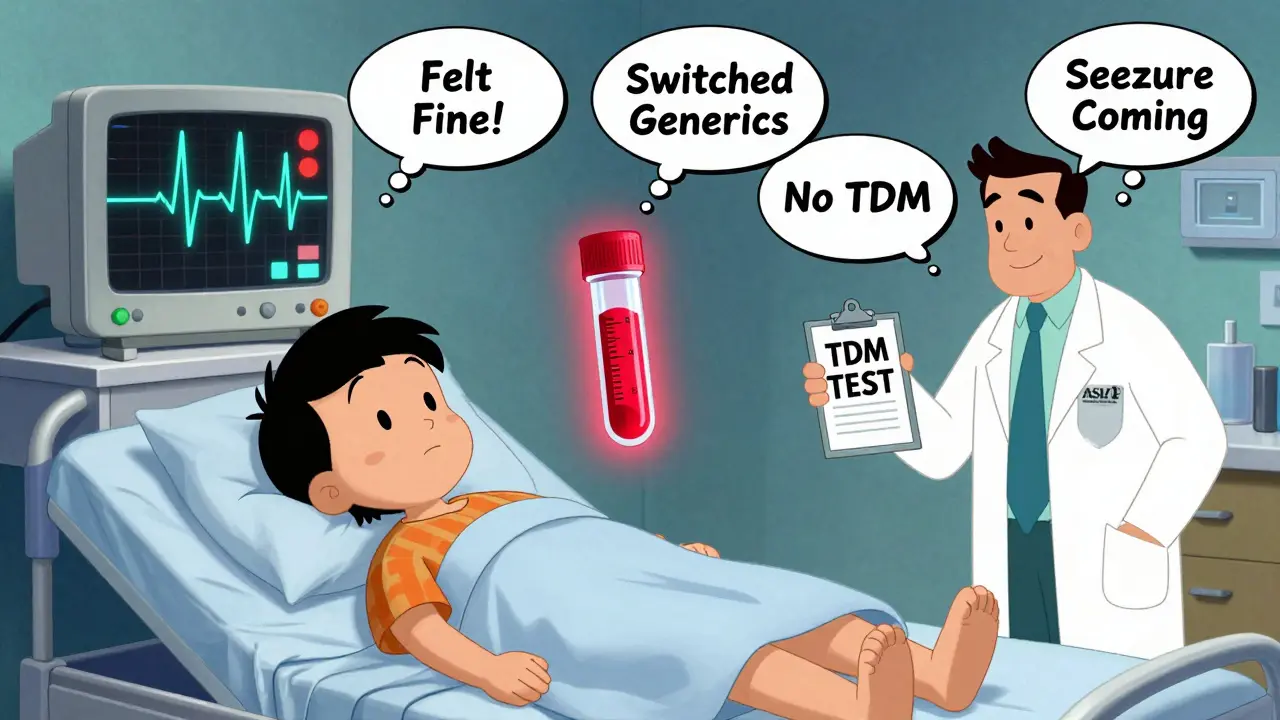

That’s a dangerous assumption. Patients on NTI drugs often feel fine-even when their levels are toxic or subtherapeutic. Symptoms like fatigue, dizziness, or nausea are vague. They get blamed on aging, stress, or other conditions. By the time a crisis hits, it’s too late.

Generic Switching: The Silent Risk

Pharmacies routinely switch generics without telling patients or doctors. Insurance plans push for the cheapest option. Pharmacists are trained to substitute, not question.

One study from the University of California found that 38% of patients on phenytoin had a significant change in blood levels after switching to a different generic version-even though both were labeled as bioequivalent. One-third of those patients had seizures within weeks.

Another case: a 68-year-old man on cyclosporine after a kidney transplant. His levels were stable on Brand X for two years. His insurance switched him to Generic Y. He didn’t notice any difference. Three weeks later, his creatinine spiked. His kidney was rejecting. TDM revealed his cyclosporine level had dropped 40%. He’d been on subtherapeutic doses for weeks.

That’s not rare. It’s predictable.

Generic manufacturers don’t have to prove they’re identical to the brand. They only have to prove they’re similar enough. For NTI drugs, that’s not enough. Blood levels matter more than pill size or color.

When TDM Works Best

TDM isn’t useful for every drug. It’s only valuable when:

- The drug has a narrow therapeutic index

- There’s a known relationship between blood levels and effect

- There’s high variability between patients in how the drug is absorbed or broken down

For NTI drugs, all three conditions are true.

TDM is most helpful in these situations:

- After switching from brand to generic or between generics

- When a patient starts or stops another medication that affects absorption (like antacids, antibiotics, or seizure drugs)

- If a patient has kidney or liver disease

- When a patient is elderly or underweight

- If a patient has unexplained side effects or treatment failure

One hospital in Ohio tracked 87 patients on warfarin who switched generics. Before TDM, 22% had an INR level outside the safe range within 30 days. After implementing routine TDM checks after every switch, that number dropped to 4%.

The Hidden Barriers to TDM

Even when doctors know TDM is needed, they often can’t get it.

Insurance doesn’t always cover it. Medicare may pay for TDM for cyclosporine in transplant patients, but not for phenytoin in epilepsy. Private insurers often require pre-authorization, which can take weeks.

Lab turnaround times are slow. In public hospitals, results can take 7-14 days. By then, damage may already be done.

And many providers don’t know how to interpret the results. A level might be "in range," but is it the right range for this patient? Is the drug being taken correctly? Are food interactions affecting absorption?

There’s also a cultural problem: many clinicians think TDM is outdated. They believe if the drug is FDA-approved, it’s safe. But approval doesn’t mean identical performance across generics.

What Patients Can Do

If you’re on an NTI drug, here’s what you need to do:

- Know your drug is an NTI drug. Ask your pharmacist or doctor: "Is this a narrow therapeutic index medication?" If they don’t know, get a second opinion.

- Ask for a baseline TDM test before any switch.

- Request a repeat test 7-14 days after switching to a new generic.

- Keep a log of your drug levels and any symptoms-fatigue, tremors, dizziness, nausea, unusual bruising.

- Don’t let your pharmacy switch your generic without telling you. Ask them to keep you on the same brand or generic version.

- If your doctor refuses TDM, ask why. If they say, "It’s not necessary," ask for evidence. Point to guidelines from ASHP or the International Society of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring.

One patient, a 52-year-old woman on lithium for bipolar disorder, switched generics three times in a year. She had no symptoms. Her doctor said, "You’re fine." She didn’t push back. Then she had a seizure. Her lithium level was 1.8 mEq/L-above the toxic threshold. She spent 10 days in ICU. Her TDM results from before the switch showed levels were stable at 0.7. The last generic she got? It absorbed 30% faster.

The Future: Better Standards, Better Monitoring

Regulators are starting to wake up. The FDA now recommends that generic manufacturers of NTI drugs provide additional data on bioequivalence-not just average absorption, but variability across populations.

Some countries, like Germany and Canada, now require TDM for all new NTI generic prescriptions. The UK’s NHS includes TDM in its guidelines for warfarin, phenytoin, and digoxin.

Technology is helping too. New point-of-care devices can measure drug levels in under an hour. Hospitals in Boston and Toronto are testing these in clinics. If they work, TDM could become as routine as checking blood pressure.

But until then, the burden falls on patients and their doctors. Generic drugs save money. That’s good. But not at the cost of safety.

For NTI drugs, bioequivalence isn’t enough. Blood levels are the only truth.

When to Call Your Doctor

Call your doctor immediately if you’re on an NTI drug and:

- You’ve switched generics and feel different-even slightly

- You’ve had a new side effect like shaking, confusion, unusual bleeding, or swelling

- You’ve started or stopped another medication

- You’ve had vomiting, diarrhea, or a major illness

- You missed doses and then took extra to "catch up"

Don’t wait. Don’t assume. Ask for a TDM test.

What does "narrow therapeutic index" mean?

A narrow therapeutic index means the difference between a safe, effective dose and a toxic dose is very small. For example, with warfarin, a slight increase in blood level can cause dangerous bleeding. With phenytoin, a small drop can trigger seizures. These drugs require careful monitoring because even minor changes in absorption or metabolism can lead to serious harm.

Are all generic drugs unsafe?

No. Most generic drugs are safe and effective. The risk is specific to narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs, where small changes in blood levels can cause harm. For antibiotics, blood pressure pills, or antidepressants, generic switches are usually fine. But for drugs like lithium, cyclosporine, or phenytoin, switching generics without monitoring can be risky.

Can I just rely on how I feel to know if my drug is working?

No. Many patients on NTI drugs feel fine even when their drug levels are dangerously high or low. Symptoms like dizziness, fatigue, or nausea are vague and often mistaken for other issues. Blood level testing is the only reliable way to know if your dose is correct.

How often should TDM be done?

TDM should be done before starting an NTI drug, after any dose change, after switching generics, and after any major illness or change in other medications. Once stable, testing every 3-6 months is common. If you’re on multiple drugs or have kidney/liver problems, testing may be needed every 1-2 months.

Is TDM covered by insurance?

It depends. Medicare and some private insurers cover TDM for drugs like cyclosporine and warfarin in transplant or anticoagulation clinics. Coverage for phenytoin or lithium is less consistent. Many insurers require pre-authorization. If your doctor says it’s not covered, ask them to appeal using clinical guidelines from ASHP or the International Society of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring.

What if my pharmacy switches my generic without telling me?

You have the right to ask for the same generic or brand name every time. Tell your pharmacist: "I’m on a narrow therapeutic index drug. I need to stay on the same version." If they refuse, ask to speak to the pharmacy manager. You can also request a written prescription that says "Do Not Substitute"-this legally prevents automatic switching.

Arjun Seth

January 14, 2026 AT 15:41This is why India's generic drug exports are a global joke-cheap, yes, but at what cost? People die because someone in a lab in Hyderabad thinks 80% bioequivalence is "close enough". No, it's not. You don't gamble with lithium or warfarin. This isn't a business model-it's negligence dressed up as progress.

Mike Berrange

January 16, 2026 AT 06:53Actually, the FDA’s bioequivalence standards for NTI drugs are outdated and dangerously lax. The 80–125% range was designed for non-critical medications. Applying it to cyclosporine or phenytoin is like using a ruler to measure a virus. The system is broken, and regulators are asleep at the wheel.

Dan Mack

January 17, 2026 AT 11:06Big Pharma and the FDA are in cahoots. They let generics in because they're paid off. The real story? The same corporations that make the brand-name drugs also own the generics. They're not competing-they're colluding. TDM isn't the solution-it's a distraction. The real fix is to ban generic substitution for NTI drugs entirely.

Amy Vickberg

January 18, 2026 AT 21:13I'm a nurse in a rural clinic, and I see this every day. Patients don't know the difference between generics. We don't have the budget for TDM. But we do what we can-educate, advocate, document. It's not perfect, but it's better than silence. We need policy change, not just patient responsibility.

Ayush Pareek

January 20, 2026 AT 12:51My uncle was on phenytoin for 15 years. Switched generics twice. No one told him. Then he had a seizure at 3 a.m. They didn't know why until they checked his levels. He's fine now, but it scared the hell out of us. If you're on one of these meds, don't wait for a crisis. Ask for the test. Keep a log. Be your own advocate. You're worth it.

Nishant Garg

January 20, 2026 AT 20:26In India, we call this "pharma colonialism"-Western companies design the rules, Indian factories produce the pills, and patients everywhere pay the price. The FDA says 80–125% is fine. The WHO says monitor. But no one says: "Make them identical." Why? Because profit loves ambiguity. Blood levels don't lie. Neither should regulations.

Nicholas Urmaza

January 22, 2026 AT 20:02Let me be clear-this is not a generic issue. This is a systemic failure of healthcare policy. TDM is not optional. It is mandatory for NTI drugs. Period. If your doctor won't order it, find one who will. If your insurance won't cover it, appeal. If your pharmacy switches without consent, demand a written "Do Not Substitute" order. Your life is not a cost center.

Sarah Mailloux

January 24, 2026 AT 00:30