There’s no such thing as a ‘generic vaccine’ - and that’s the problem

When you walk into a pharmacy and pick up a generic version of your blood pressure pill, you expect it to cost a fraction of the brand-name version. It’s the same active ingredient, same effect, same safety profile - just cheaper. That’s how generics work for small-molecule drugs. But with vaccines? It doesn’t work that way. There are no true ‘generic vaccines’ in the way we understand generics for pills. That’s not because no one is trying. It’s because the science, the manufacturing, and the supply chains make it nearly impossible.

Vaccines aren’t chemicals you can copy-paste. They’re complex biological products. Think of them like a living recipe: live viruses, modified mRNA, proteins grown in cell cultures, adjuvants, stabilizers - all needing perfect conditions to work. Even tiny changes in temperature, pH, or purification steps can ruin the whole batch. That’s why regulators like the FDA and EMA don’t accept abbreviated approval paths for vaccines the way they do for pills. You can’t just prove ‘bioequivalence.’ You have to rebuild the whole thing from scratch, with full clinical trials and manufacturing validation. It’s not a shortcut. It’s a full rebuild.

Who makes the world’s vaccines - and why it’s so concentrated

Just five companies - GSK, Merck, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson - control about 70% of the global vaccine market. That’s $38 billion in 2020, and most of it flows through a handful of factories in Europe and North America. But here’s the twist: India produces 60% of the world’s vaccine volume by dose count. The Serum Institute of India alone churns out 1.5 billion doses a year. It’s the biggest vaccine maker on Earth. Yet, it doesn’t own the patents. It manufactures under license - mostly for Western companies.

India’s strength lies in scale and cost. It supplied 90% of the WHO’s measles vaccine and 70% of its DPT doses. During the pandemic, it made the AstraZeneca shot for under $4 per dose - while Western producers charged $15-20. But here’s the catch: even at that low price, margins were razor-thin. Building a single vaccine production line costs $500 million. The factory needs biosafety level 2 or 3 containment, ultra-cold storage, and specialized equipment you can’t buy off the shelf. Only five to seven global suppliers make the lipid nanoparticles needed for mRNA vaccines. If one of them shuts down, the whole pipeline stalls.

The supply chain is a single point of failure

During India’s second wave of COVID-19 in April 2021, the country halted vaccine exports to prioritize its own population. That single decision cut global vaccine supply by an estimated 50%. Why? Because even though India makes most of the doses, it imports 70% of its vaccine raw materials from China. When China restricted exports of key ingredients, Indian factories couldn’t keep up. Meanwhile, the U.S. banned exports of critical components like bioreactor bags and filters, fearing domestic shortages. The world’s vaccine supply chain wasn’t resilient - it was brittle.

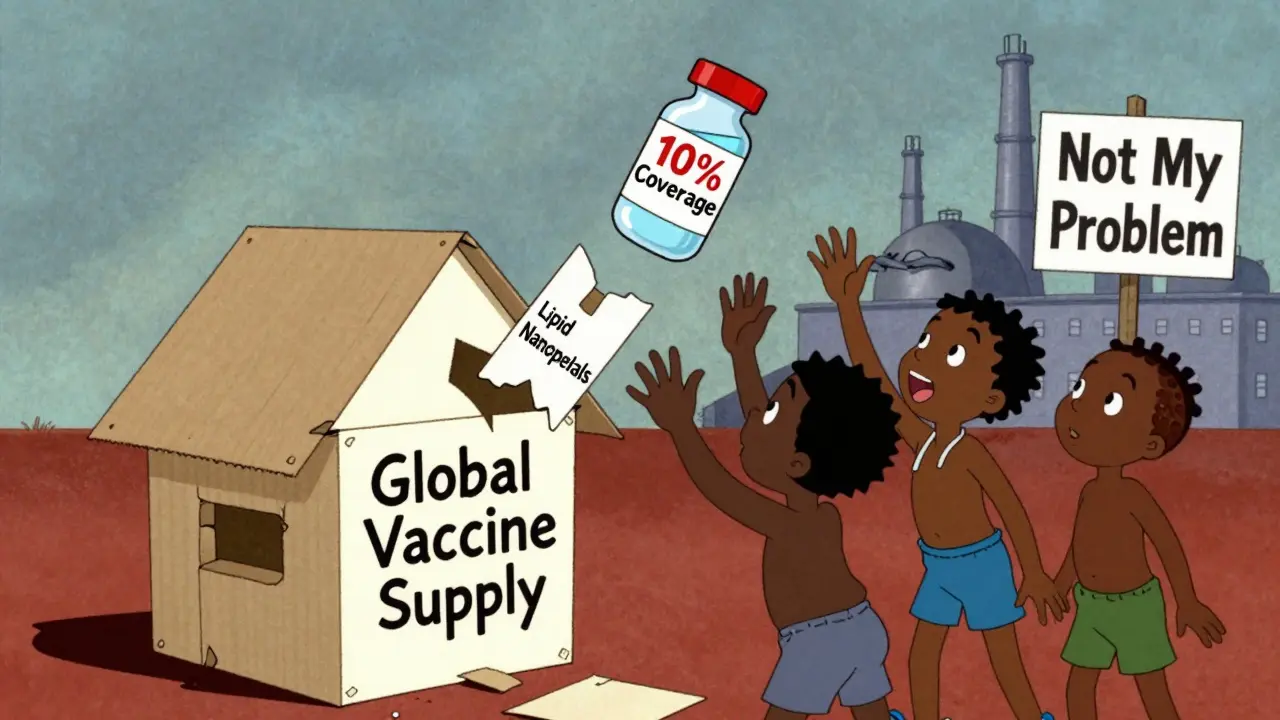

It’s not just raw materials. The cold chain is a nightmare. mRNA vaccines need to be stored at -70°C. Most clinics in rural Africa, Southeast Asia, or Latin America don’t have freezers that cold. Médecins Sans Frontières reported that in April 2021, 83% of all COVID-19 doses delivered to Africa went to just 10 countries. The other 23 African nations had vaccinated less than 2% of their people. Some doses arrived with only two weeks left before expiration - and no way to use them before they spoiled.

Why low-income countries are still stuck importing 99% of their vaccines

Africa produces less than 2% of the vaccines it uses. Nine out of ten vaccines used on the continent are imported. That’s not because Africans can’t make them. It’s because no one invested in the infrastructure. The African Union estimates it will take $4 billion and 10 years to get to 60% self-sufficiency. That’s a long time - and no one’s giving the money upfront.

Meanwhile, the WHO set up a mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub in South Africa in 2021, with technical help from BioNTech. Two years later, it produced its first batch. But it’s only capable of making 100 million doses a year. That’s less than 1% of global demand. The delay? Getting the right equipment. Sourcing the right lipids. Training the right technicians. Even with the blueprint, the real-world barriers are too high.

India’s experience shows that volume doesn’t equal control. The country has over 500 API manufacturers and supplies 14% of U.S. generic drugs. But when it comes to vaccines, it’s still playing catch-up on the upstream side. The raw materials, the equipment, the expertise - it’s all concentrated in a few places. And when those places decide to prioritize their own needs, the rest of the world pays the price.

Price isn’t the issue - access is

People think the problem is price. That if only vaccines were cheaper, everyone could afford them. But the real problem is access - and control. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, negotiated with manufacturers to offer lower prices to low-income countries. But even then, the pneumococcal vaccine still cost over $10 per dose - far above what health systems in rural areas could realistically pay. Meanwhile, manufacturers didn’t share technology. They didn’t license patents broadly. They didn’t help build local capacity.

Compare that to generic drugs. Once a patent expires, dozens of companies enter the market. Prices drop 80-90%. Competition drives down cost. But with vaccines? There’s no competition. There’s no ‘generic’ market. There’s one or two producers. And they set the price. If you’re a low-income country and you need a vaccine, you either take what’s offered or wait. And wait you do - often for years.

What’s being done - and why it’s not enough

The U.S. FDA launched a pilot program in 2025 to speed up approval for generic drugs made and tested domestically. Why? Because 9% of API manufacturers are now in the U.S. - down from 22% in China and 44% in India. The FDA admits: overreliance on foreign manufacturing creates national security risks. But this pilot only applies to pills - not vaccines. The same logic doesn’t extend to biologics.

Some argue that public funding could fix this. The Gates Foundation says the answer is simple: expand manufacturing. But they also admit it’s expensive. Building a vaccine plant takes 5-7 years and half a billion dollars. That’s not a cost governments or NGOs can absorb quickly. Even if they did, the training, the supply chains, the regulatory approvals - they take time. And time is what people in low-income countries don’t have.

India’s ‘Vaccine Maitri’ initiative sent doses to over 100 countries during the pandemic. But when India needed those doses for itself, the exports stopped. That’s the reality of a global system built on charity, not equity. When push comes to shove, countries protect their own. And the world’s most vulnerable are left behind.

The path forward isn’t about copying - it’s about building

There won’t be a ‘generic’ version of the mRNA vaccine anytime soon. But there could be more local producers. Not copycats. Not licensees. Real manufacturers - with their own tech, their own supply chains, their own control.

That means investing in African and Southeast Asian factories, not just donating doses. It means transferring not just the recipe, but the tools, the training, and the trust. It means paying for equipment, not just pills. It means letting countries like India and South Africa lead, not just follow.

It’s not about making cheaper versions of what exists. It’s about building new systems - ones that don’t depend on a handful of companies in a few countries. Because right now, the world’s vaccine supply is like a house of cards. One country shuts its borders, one supplier runs out of lipid nanoparticles, one freezer fails - and millions go unprotected.

The solution isn’t more charity. It’s more capacity. More ownership. More local control. Until then, vaccine equity will remain a slogan - not a reality.

Ron Williams

December 15, 2025 AT 13:48Man, this post really lays it out. I never thought about how vaccines aren't like pills at all. It's not just about the chemistry-it's the whole ecosystem. Cold chains, lipid nanoparticles, bioreactors... it's like trying to replicate a symphony with a kazoo. And yeah, India's doing the heavy lifting but getting squeezed by supply chain choke points. We're all just one broken freezer away from chaos.

Kitty Price

December 16, 2025 AT 19:08So basically we're all stuck playing Jenga with global health 😅

Arun ana

December 17, 2025 AT 19:14As someone from India, I see this every day. We make billions of doses but don’t own the tech. The factories? They’re ours. The machines? Mostly imported. The lipids? From China. The patents? Locked up in Zurich or New Jersey. We’re the factory workers of global immunity-no credit, no control, just exhaustion. And when we needed our own vaccines during the wave, the world didn’t help. They just waited.

Kayleigh Campbell

December 18, 2025 AT 03:06Oh honey, let me get this straight-we’ve got a world where you can order a drone to your porch in 2 hours, but if you’re in Malawi, you gotta beg for a vaccine that expires in 14 days because no one bothered to install a freezer? 🤦♀️ The real pandemic is laziness. We’d build a Mars colony faster than we’d build a vaccine lab in Lagos. It’s not about money. It’s about who we decide matters.

Joanna Ebizie

December 19, 2025 AT 11:03Y’all are overcomplicating this. It’s simple. The West doesn’t want cheap vaccines because then the third world won’t need us anymore. They’d rather let people die than lose their monopoly. It’s capitalism, dumbass. Stop pretending it’s about science.

Elizabeth Bauman

December 20, 2025 AT 22:16China and India are stealing our vaccine tech through backdoor deals. That’s why the U.S. had to ban exports of bioreactor bags-because our own supply chain was being drained by foreign rivals. We’re not being selfish, we’re being strategic. If we let Africa build their own labs, they’ll outproduce us and then demand we pay them for the rights to use OUR science. This is economic warfare. Wake up.

Dylan Smith

December 22, 2025 AT 05:34the fact that we still think vaccines are like pills is wild. you cant just copy a recipe if you dont have the oven the heat source the ingredients the chef the delivery truck the fridge the power grid the trained workers the regulatory body the trust of the people. its not a product its a whole damn civilization working together. and we built it on sand

Mike Smith

December 23, 2025 AT 13:16Let me be clear: vaccine equity is not a charitable endeavor-it is a strategic imperative. The global health architecture we have inherited is fragile, inequitable, and unsustainable. To invest in local manufacturing capacity in low- and middle-income countries is not merely an act of goodwill; it is an investment in global security, economic resilience, and scientific sovereignty. The time for incrementalism has passed. We require bold, coordinated, and adequately funded action-not donations, but partnerships. Not licenses, but legacy. Not charity, but capacity. The world does not need more doses. It needs more doors.